Chester County Detective Roy Calarese working in the Chester County District Attorney’s Computer Forensic Lab.

A 20 year old man is found shot to death in a car. No witnesses. No weapon. How do police start to figure out who did it?

One key is to determine what the victim was doing and who he had contact with directly before the murder. That may involve investigators painstakingly re creating the victim’s activities through dozens of interviews with family and friends, reviewing hours of video from local businesses and homes, and pursuing multiple other leads.

Or the investigators can simply check the victim’s mobile phone. Today’s average smartphone will contain all of the clues about who the victim was talking to, where he has been, and what he was doing until the body was discovered. The same information can be pulled from a potential defendant’s phone. And because virtually everybody now carries a mobile phone, the ability to extract data from electronic devices has become a critical tool in modem law enforcement.

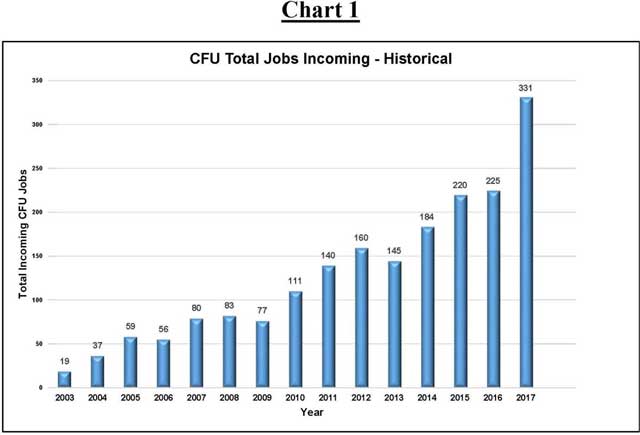

Addressing this tremendous change in technology, the Chester County District Attorney’s Office maintains a Computer Forensics Unit (the “CFU”) to deal with digital evidence. The CFU was created in 2003. The CFU processes electronic devices for all 46 police agencies in Chester County, and handles all electronic evidence for the District Attorney’s Office. From 19 jobs handled in 2003 through 331 jobs in 2017, the CFU has dealt with an ever-expanding case load.

“Computer forensics is a growing and vital field for law enforcement,” Chester County District Attorney Hogan said. “Whether we are investigating drug dealing, child pornography, white collar fraud, or violent crimes, the ability to retrieve and interpret electronic data is crucial. We are lucky to have such resources available in Chester County.”

The CFU is housed in a special computer forensics lab in the Chester County Justice Center. Such a lab requires sophisticated computer hardware and software, electronic storage capacity, and a climate-controlled environment. The Chester County Commissioners authorized the construction of the new lab in 2014.

“Modem law enforcement needs the ability to deal with electronic evidence. In order to protect our citizens, Chester County is proud to have an outstanding computer forensics lab and investigators,” Chester County Commissioner Terence Farrell said.

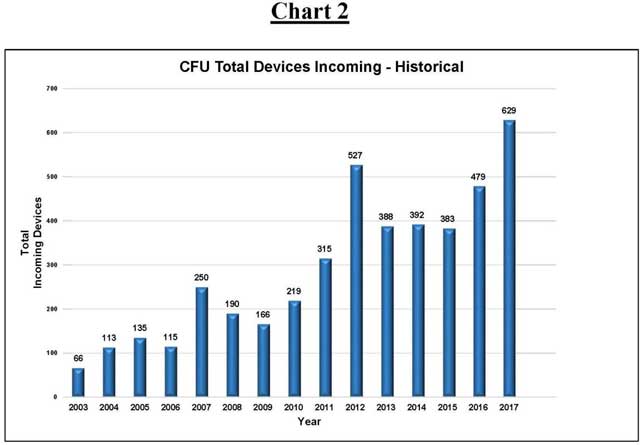

The explosive growth in the field of computer forensics can be seen in the total number of jobs and devices handled by the CFU every year. A job is considered a single case, which may include multiple devices to be examined. For instance, one child pornography investigation will be shown as one “job,” but may involve the examination of three computers and four phones, meaning one job with seven devices.

The following charts show the tremendous increase in work done by the CFU in criminal cases:

“The technology in computer forensics is constantly evolving,” Chester County Detective Roy Calarese, the lead investigator for the CFU, added. “A smart phone today has more functions and storage capabilities than a full-size desktop computer in 2003. We like the challenge of staying on top of the technology and using that technology to catch the bad guys.”

The Chester County District Attorney’s Office also partners with the FBI’s Regional Computer Forensics Laboratory (the “RCFL”). The RCFL is an FBI facility that merges the personnel and equipment of the FBI with local law enforcement. The District Attorney’s Office has an investigator assigned to the RCFL, as do the other suburban District Attorney’s Offices.

“The FBI is committed to working with our law enforcement partners. Computer forensics is at the cutting edge of global law enforcement,” FBI Supervisory Special Agent John “Jack” Martinelli, the director of the RCFL, said. “Combining the FBI’s assets with our local partners makes all of us better at fighting crime.”

One of the major issues for both the Chester County CFU and the FBI RCFL is what is called the “Going Dark” problem. “Going Dark” refers to technology companies intentionally creating security or encryption for electronic devices that cannot be pierced even with court-approved search warrants. This means that criminals can use certain devices or programs without any danger of the police being able to discover the communications.

For instance, a drug dealer might use Snapchat to send and receive orders for heroin. Even if law enforcement manages to arrest the defendant and seize his phone, all of the Snapchat data has either been destroyed or is encrypted, effectively hiding the drug dealer’s illegal conduct forever. And that assumes that law enforcement is even able to get beyond the initial locked security settings on the phone.

“Somebody once joked that the three main user groups for encrypted messenger services are: (1) teenagers who are hiding conversations from their parents; (2) drug dealers; and (3) terrorists,” Hogan said. “Law enforcement does not care about the secret teenage conversations, but the clandestine communications of the drug dealers and terrorists must be subject to lawful discovery, or we cannot protect the public.”